Hello again, fellow readers. Today I’ll cover what are basically the building blocks of my future work: the ZeroMQ sockets.

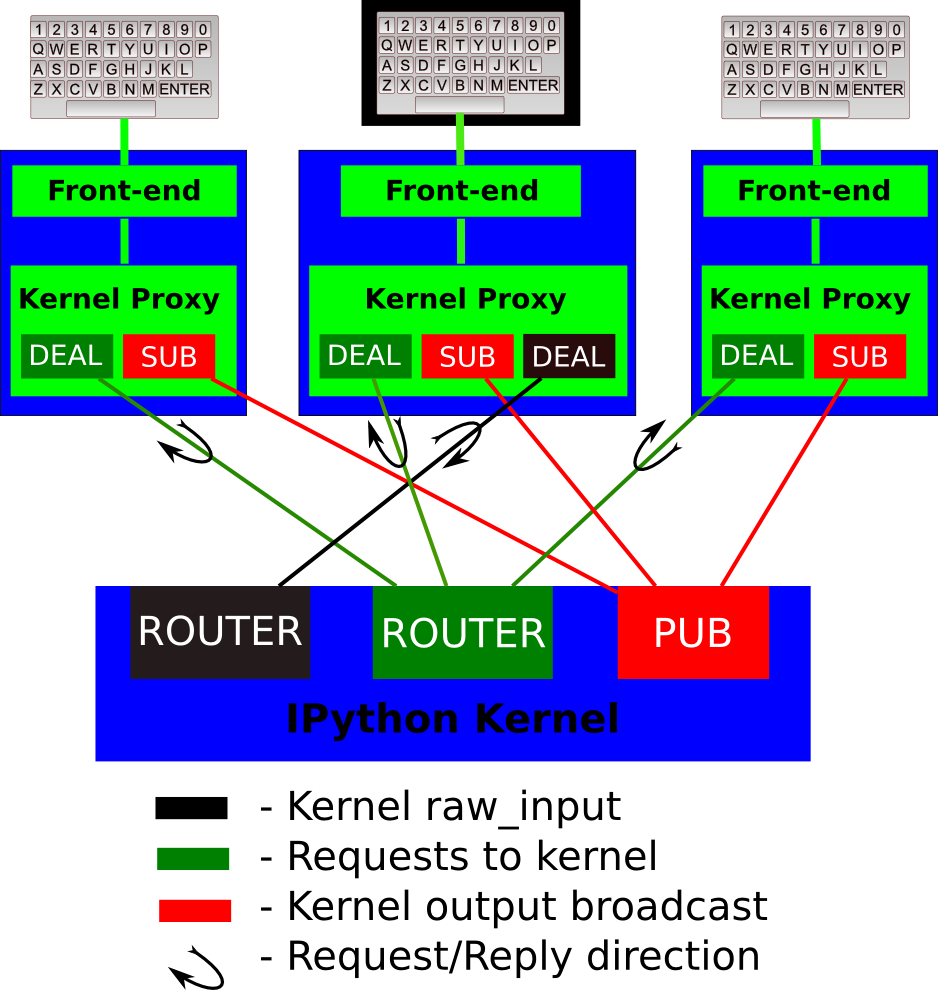

As I briefly commented on my previous post, Jupyter works through the interprocess communication between multiple frontends and backends, enabling access to different programming languages from the same user interface. Let’s recap:

(The example above shows the IPython kernel, Jupyter backend implementation for the always nice Python language [if you didn’t know it, I really recommend that you learn about it]. That happens because IPython is the reference implementation [actually, Jupyter came from an split in the IPython project], but the same applies to any other language backend.)

So, these communications are performed through ZeroMQ connections.

“But what is it, exactly ?”

Well, I could try to explain this myself, but I’ll show you the “In a Hundred Words” definition from the ZGuide:

ZeroMQ (also known as ØMQ, 0MQ, or zmq) looks like an embeddable networking library but acts like a concurrency framework. It gives you sockets that carry atomic messages across various transports like in-process, inter-process, TCP, and multicast. You can connect sockets N-to-N with patterns like fan-out, pub-sub, task distribution, and request-reply. It’s fast enough to be the fabric for clustered products. Its asynchronous I/O model gives you scalable multicore applications, built as asynchronous message-processing tasks. It has a score of language APIs and runs on most operating systems. ZeroMQ is from iMatix and is LGPLv3 open source.

So, basically, it’s a library for passing messages between programs (or inside programs, between threads) in an asynchronous way, which means: when you send a message, the program doesn’t wait (block) for the operation (which could be a relatively costly system call) to complete. Instead, the messages are put on a queue and a background thread gets the dispatch job done when possible (a.k.a. CPU is available). Receiving data works in a similar way: the background thread listens for incoming messages and enqueues them for fast reading when you request it (obviously, if you don’t receive data your read queue gets empty and a read operation blocks the program, so the data availability should be checked).

(Well, I guess I ended up explaining it with my own dumb words anyways…)

The result is that ZeroMQ helps (or even forces) you to design you application with concurrency and parallelism in mind, which is useful in today’s multicore and distributed computing world.

Not only this: ZeroMQ also comes with some built-in communication patterns/protocols, that let you setup you network topology quicker. See those “DEAL”, “ROUTER”, “PUB” and “SUB” labels on the diagram above ? They represent some of them:

- The Router-Dealer pattern: A Router adds an identifier to messages comming from Dealer or Request sockets, so you know where it came from, and where to send a message back (by prefixing the response with the same identifier). Similarly, a Dealer can connect to multiple Router or Reply sockets for messages exchange.

- The PUB-SUB or Publisher-Subscriber pattern: A Publisher is a write-only socket capable of sending the same message to all sockets subscribed to it in a single call, specifying a topic header/prefix. Complementarily, a Subscriber is a read-only component that can filter incoming messages (from the publishers it is connected/subscribed to) based on its topic.

Other protocols (like Request-Reply and Pipeline) are listed on the lengthy and informative ZGuide (by the way, considering how much documentation tends to suck in the open source world, I was surprised by how much information one can find on the ZeroMQ related websites).

For someone who already worked quite a bit with low-level BSD Sockets and system threads programming, what ZeroMQ provides (from what I could already learn), frankly speaking, is both great and strange: its socket-like API looks familiar and gives me an impression of knowing what is happening, but the way it enforces limited options for communication patterns is kinda difficult to digest when you are used to build your own thing. However, GSoC is about learning new things, possibly how to do something better, and I should be willing to open my mind to different approaches for a problem (If in the end it doesn’t convince me, maybe I could try contributing code and ideas to ZeroMQ itself, lol).

That said, it looks like I’m not alone with this initial reaction, and the ZeroMQ developers are so aware of that that they even provided access to raw TCP sockets, allowing stubborn people like me to get a handle of how things work in a more gradual way.

This motivated me to write some test code (actually, it’s a modified example):

//

// "Hello World" server in C++

// Binds STREAM socket to tcp://*:5555

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

#ifndef _WIN32

#include <unistd.h>

#else

#include <windows.h>

#define sleep(n) Sleep(n)

#endif

int main()

{

// Every ZeroMQ application should create its own unique context

zmq::context_t context( 1 );

// Creating a raw TCP socket (yay!)...

zmq::socket_t socket( context, ZMQ_STREAM );

// ...and using it to listen for messages on port 5555

socket.bind( "tcp://*:5555" );

while( true ) // Run forever

{

zmq::message_t request; // Message object. Stores network data

// Wait for next message from client

socket.recv( &request );

// Show what we got

std::cout << "Received: " << (char*) request.data() << std::endl;

// Do some 'work'

sleep( 1 );

// Build reply message and send it back to client

zmq::message_t reply( 5 );

memcpy( reply.data(), "Hello", 5 );

socket.send( reply );

}

return 0;

}While this code is running and I send a message from another terminal with the shell command (sorry, Linux guy here):

# Just send the "Hi" string through a TCP client connected to localhost (127.0.0.1) and the server port (5555)

echo -n "Hi" | nc 127.0.0.1 5555I can see the server output:

Received:

Received: Peer-Address

Received:

Received: Hi

Received:

Received:(A lot of empty messages. Delimiters, according to the docs. I don’t know if ZeroMQ performs some underlying optimizations, packing messages in a single data transfer or something like that, but that’s how it is)

As you can see, the code is written in C++, like the core ZeroMQ library. Even if there’s bindings for a lot of other languages (as C, Python, C#, Java, Ruby, PHP, Go, Lua, etc.), that’s what I’ll be using for building the Jupyter kernel, because it’ll be easy to interface with the Scilab C++ API, and that means less abstraction layers (I like things leaner).

I guess that’s it for now. Next time I’ll try to bring you more details about the kernel implementation and calling Scilab libraries.

See ya !